Last week I went to

Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico in San Francisco's De Young Museum. It was a splendid exhibition of the staggering artistic achievement of the Olmecs.

A little background first. The Olmecs are often called the mother culture of Mesoamerica, its florescence between 1800 and 400 BCE in the swampy areas of the Gulf Coast of Mexico, in particular the states of Veracruz and Tabasco. They were the first people of North America to really experiment with creating large monument works, both architectural and sculptural. And their view of the cosmos and the iconography to represent it became so pervasive in Mesoamerica that it even could be found as far away as Costa Rica.

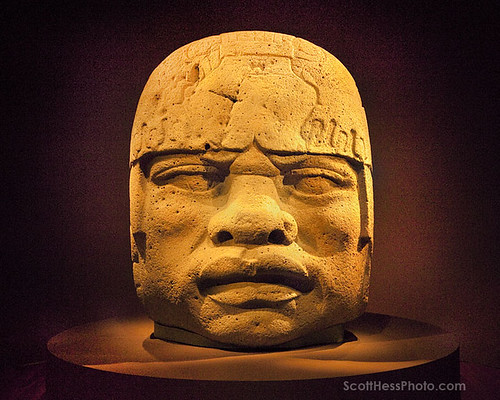

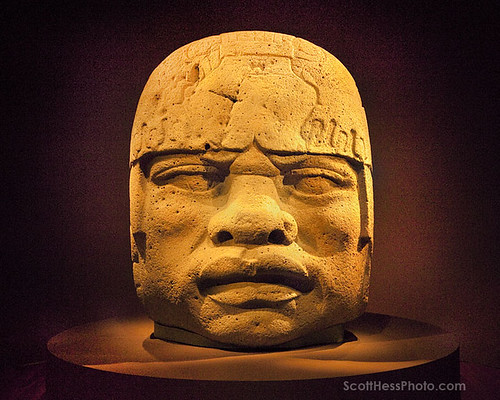

The special exhibition area of the museum is entered via a tunnel. As I turned the corner I was immediately greeted by the impassive face of a colossal head, the massive stone carving of an Olmec ruler from the first site of San Lorenzo made between 1200 and 900 BCE. It was 6 feet by 4.7 feet by 4 feet (1.86m by 1.44m by 1.25m), and made quite an impression on me. Even the name is enigmatic, simply called Colossal Head 5 by archaeologists.

Obviously I could not take picture due to the exhibit's policy but professional photographers can and are willing to share, which is what you see above.

In addition to Colossal Head 5 there were many other large stone sculptures at the exhibit. Many were in the form of Olmec shamans in kneeling poses captured in the middle of a ritual, such as

Monument 9 of El Azuzul. There were also fantastic zoomorphs, fierce combinations of different animals and humans, such as

Monument 7 of El Azuzul, a fierce jaguar-human supernatural being. More over, what is really interesting is that Monument 9 and its twin Monument 8 were discovered facing Monument 7, the jaguar supernatural. Perhaps they were supplicating themselves in front of the jaguar deity.

A few of the great monuments contain some of the earliest writing in Mesoamerica. I was very happy to finally see Stela C of Tres Zapotes, which contains a Long Count date corresponding to 32 BCE. It is one of the few examples of the

epi-Olmec writing system.

(Note image is not from the exhibit but from the Smithsonian Institute)They also had the

Stela 3 of Chiapa de Corzo, with an even older date of 36 BCE. I was amazed that they even call it a stela because it was quite small. The one fragment was no bigger than an iPad! One exciting thing about this "stela" is that there is currently a very active excavation at this ancient city, and just last year the team discovered the oldest royal burial inside a pyramid, and I expect in upcoming years to hear of discoveries of new epi-Olmec texts.

There were also other examples of monumental writing, like Monument 13 of La Venta, also called "Ambassador Relief". Its dating is very controversial, ranging from 1000 to 400 BCE. Its glyphs are also much different than epi-Olmec glyphs. Perhaps it is an older writing system that we know nothing about.

The last inscribed monument was the

Chapultepec Stone. Although of unknown provenance, it is thought to be from the Late Classic period, between 500 and 800 CE, almost a thousand years after the Olmecs. Its inscriptions are completely unknown and unlike anything else, although given its location is it might be a late form of the epi-Olmec script. It is certainly another enigma to be tackled by future archaeologists.

While the colossal heads, full-size sculptures, stelae carved with text, and other stone works truly embody the "colossal" character of the exhibit, a substantial portion was dedicated to small-scale, portable objects as well. In particular, green stones like jade were prized by the Olmecs (and Mesoamericans in general) for its brilliant blue green hue and symbolic of life. It was carved into myriads of shapes and forms, from simply ceremonial axe heads to human portraits.

The jade piece on the left is called the Kunz Axe (after its discoverer) and depicts the so-called "werejaguar", originally thought to be a combination of human and jaguar aspects but more recently thought to be a human-reptilian conflation.

The piece on the right is a "celt", a ceremonial axe, and likely hung from a lord's belt (note the hole on the bottom that rope possibly went through). The carvings on it are very hard to discern but they represent the Olmec maize god, as identified by cruciform maize sprouting from its cleft head. The downturned mouth, also present in the Kunz Axe, is a prominent motive in Olmec art to mark deities, and even later Zapotec and Maya cultures continued this tradition. In fact compare the Olmec maize god to

the Maya maize god on the San Bartolo murals and you'll see that they are basically the same.

It would seem that all the Olmecs ever carved were formal, rigid works displaying political and religious iconography. While certainly quite true for a majority of the artifacts, there is a small number of Olmec carvings that display remarkable humanity.

Take, for instance, my wife's favorite piece of the exhibition, very simply titled "Fragmentary Figure". As you can see in the picture above, it is quite broken, but fortunately the head is intact and one can almost feel a serious tension emanating from the character's face. There is also remarkable refinement and individualism in its facial features.

A jade

statuette from La Venta depicts a woman with a hematite mirror on her chest. Sexist jokes aside, the mirror was in fact a symbol of power. This piece was found in a burial, and while the bones did not survive the acidic soil of La Venta, it means that the statuette was possibly buried with an elite lady who held some sway in Olmec politics. However, what intrigued me the most is her enigmatic smile, quite different than the typical scowl of Olmec sculptures.

However, this lady has nothing on the biggest smile of them all. There was a second colossal head in the exhibition, Colossal Head 9 of La Venta, who stood at the last room of the exhibition.

Who knows why this colossal head is smiling while its companion at the entrance showed a poker face? Maybe there was a reason or maybe the ruler who commissioned the work just felt like it. One thing we tend to forget about ancient people is that they have the same cacophony of emotions, needs, and opinions as we do. I think even the stone-faced Olmecs sometimes have to let loose a bit.

PS. Even though the Olmecs lived thousands of years ago, they left a legacy that permeated into later times and even into modern Mexico. After spending the morning staring at impressive stone sculptures my wife and I decided to go to our favorite Mexican restaurant in San Francisco,

Nopalito. (No I am not turning this into a food blog. There is a point to this.) One dish we got was their excellent

enchiladas de mole con pollo, the chocolate nicely prominent in this most Mexican of sauces. However, did you know that the other word for chocolate,

cacao, originally came from the ancient Zoque language, the language most likely spoken by Olmecs? Say "cacao"...You just spoke Olmec! See, there

is a point to this tangent.

What is this boustrophedon thing you ask? It's not some high-tech fancy gadget, but instead an ancient way of alternating the direction of writing. In the history of the Greek alphabet, there was a transitional period between the right-to-left direction inherited from Phoenician and the better known left-to-right direction where texts were written in both directions, alternating every line. The letters themselves appeared mirrored depending on the direction of writing.

What is this boustrophedon thing you ask? It's not some high-tech fancy gadget, but instead an ancient way of alternating the direction of writing. In the history of the Greek alphabet, there was a transitional period between the right-to-left direction inherited from Phoenician and the better known left-to-right direction where texts were written in both directions, alternating every line. The letters themselves appeared mirrored depending on the direction of writing.  Rongorongo tablets employed an even more extreme for of boustrophedon called reverse boustrophedon. The glyphs are mirrored both horizontally and vertically, or in other words, rotated 180° every line. The idea, perhaps, was to read one line, turn the tablet 180° upside-down and read the next line. On the example to the left, you can see that the brown glyphs are the same on both line, but they are upside down and mirrored. If anything, this style of boustrophedon fits the meaning of the name much better because the ox and the farmer really do turn 180° each time.

Rongorongo tablets employed an even more extreme for of boustrophedon called reverse boustrophedon. The glyphs are mirrored both horizontally and vertically, or in other words, rotated 180° every line. The idea, perhaps, was to read one line, turn the tablet 180° upside-down and read the next line. On the example to the left, you can see that the brown glyphs are the same on both line, but they are upside down and mirrored. If anything, this style of boustrophedon fits the meaning of the name much better because the ox and the farmer really do turn 180° each time.  And somebody precisely thought of this principle 3700 years ago. The Phaistos Disc (pictured to the right) is a one-of-a-kind artifact, the only example of a stamped text starting from the outside of the disc and spirals inward in a counterclockwise direction until the text terminates at the very center of the disc. Actually the disc is still undeciphered. The direction of writing is inferred from physical characteristics of the signs themselves.

And somebody precisely thought of this principle 3700 years ago. The Phaistos Disc (pictured to the right) is a one-of-a-kind artifact, the only example of a stamped text starting from the outside of the disc and spirals inward in a counterclockwise direction until the text terminates at the very center of the disc. Actually the disc is still undeciphered. The direction of writing is inferred from physical characteristics of the signs themselves.